Writing’s Infamous Counterpart

What does it mean to write in the digital age? What does that look like, how does it differ from writing practices of the past?

Content. This is a word that has made its way to the forefront and changed the way people view information, news, data, writing, creative activity, you name it. In the article, When Writing Becomes Content, author Lisa Dush, examines the word content as primarily being synonymous with writing. She defines content by providing four features associated with its digital asset nature (conditional, computable, networked, and commodified). She then elaborates on the digital age, how it allowed the development and expansion of this metaphor, and ponders whether teaching it will have a permanent placement in writing study programs as it holds certain limitations and concerns.

Analysis

On the topic of defining content, Dush argues, “Content has a core conditional quality, fluidity in terms of what shape it may take and where it may travel, and indeterminacy in terms of who may use it, to what ends, and how various uses may come to be valued,”(176).

Here, the author suggests that writing for today’s environment is complex as it involves keeping in mind much more than the art of writing once did. It involves understanding the dynamics of the four characteristics of content, as well as producing work that will accommodate various platforms (instagram, twitter) but also tech , i.e. mobile, computer, etc.

Figure 1.1

The way Journalism is taught today, through courses such as: the Fundamentals of Online Journalism, Data Journalism, and Visual Communication, supports the author’s claim of writing becoming content-driven. The notion of content being contingent, is based on what you are communicating, and how you are communicating it, and where you are communicating it. Ergo, content allows information to have much more of an impact than simply using words on paper.

That is not to say the art of writing is dead… as Dr. Kperogi, my Feature and Magazine Writing course instructor once said, people love anecdotes, and stylistic writing is what helps those stories resonate with a myriad of people.

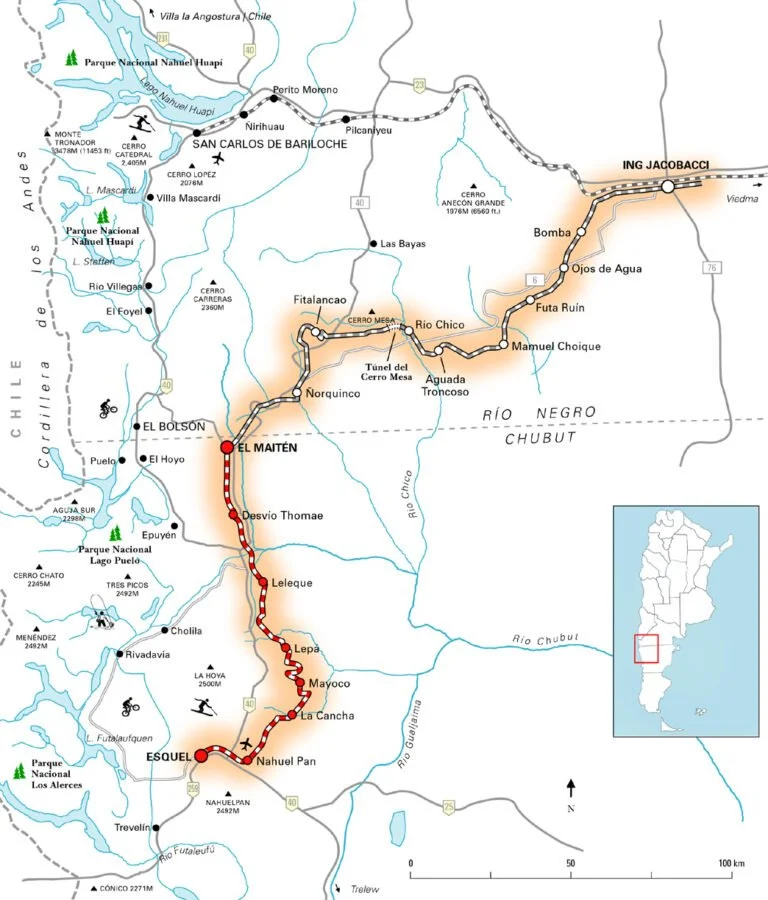

However, what Dush is saying is that the manner in which those stories are presented can also increase the exchange value (value based on profit) of said content, making it commodified. Adding a map that shows the dotted route a person gone missing went on can further elucidate information that would otherwise be given in word form (use value). For instance, each dot could be clicked on to show each stop that was made along with the specific time stamp. This change from words to dots on a map (illustrating the conditional quality of content) can increase the comprehension of facts and the time a viewer spends interacting with an article (use value + exchange value).

This idea of delivery, and ways to convey content, is similar to what Dush mentions as multimodal writing, similar to Jodie Nictora’s “textual object,” (261). With the writing-as-content mind-frame, it pushes journalists to think creatively, yet critically when it comes to presenting deliberate information to the public.

In parallel, Dush states, “It moves us beyond a focus on the designed document and its digital equivalent, the text designed for screen display, and attendant concerns with modal affordances (i.e., what images do well, what words do well),” (181). In the field of journalism, the following question would be asked: What is the best way to tell this story? Visuals, audio clips, written statements?

I do believe content has become synonymous with writing, as they both involve the gathering and collecting of ideas. Another word that is frequently being used to describe the writing profession today is storytelling. Much of the content online has been wrapped around the ability to tell a compelling story; whether selling a product, shining a light on social reforms, or merely uploading personal vlogs on the internet, stories are being used to capture the attention of a large audience.

Writing and content, when separated, contain several differences, and towards the end, Dush questions whether their differences can encourage or threaten the end result. Writing for example is idiosyncratic and unique to every writer, content however, becomes standardized to appeal to a wide audience. Writing comes in the form of a document, while content takes the shape of assets. Thus, does the asset aspect help with keeping reader’s informed, or does it result in misuse and misconduct?

Dush effectively discusses when writing becomes content by reminding the reader the sphere in which these concepts exist. Ample information is given on digital assets and their components that allow for communication with both humans and machines. The author provides new ways to think about composing text and reasons to support but also question the use of content in place of writing.

“Ultimately, the risks of ignoring writing-as-content or, likewise, dismissing it, are that we may miss an important opportunity to expand the conceptual, research, and pedagogical purview of writing studies in ways that are appropriate to the digital age,” (193). This metaphorical lens- understanding writing as content- enables readers to have some kind of groundwork to assess these findings and outlooks.

Works Cited

Dush, L. “When Writing Becomes Content.” National Council of Teachers of English (2015): 173-196.